In the spirit of documenting some of my coursework on this blog, I thought I’d share one of my favorite assignments from this past semester. In my recent U.S. Housing Policy course with former FHA head Carol Galante, we were tasked with developing a mock set of 5 recommendations for addressing the housing affordability crisis through land use reform in the Bay Area. The assignment got me fantasizing a lot about my top 5 policies—no matter how politically feasible. Below, I present three local policies, one state, and one federal policy that are my top 5 land use reform policies for housing affordability. Obviously there are some other high-level reforms (e.g. providing housing as a human right) that I could include here, but sticking with the theme of land use reform is more in my wheelhouse and a more manageable set of possible reforms.

Local Recommendations

At the local level, the rules of the housing development process are largely set in stone by state level policies. However, localities in the Bay Area often make the process more difficult and costly than even state policies demand. Therefore, two of my fantasy local policy recommendations represent common sense reforms (at least among city planners) to make development easier and less costly. The third local reform—land value taxation—is a progressive tax to redistribute the wealth from well-endowed landowners to the general public, who create the social value of the land.

I. More Ministerial Development Approval

For many localities in the Bay Area, the general parameters of the city planning process are largely prescribed by the state. For example, localities must make general plans where they plan which areas of the city can receive future housing growth and zoning decisions must conform to these plans. Furthermore, each locality must review the environmental impacts of housing developments to ensure that they comply with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). This process is already quite extensive and onerous as is. Yet, many localities in the Bay Area make this process even more burdensome by not allowing ministerial approval—that is, approval that is dependent on the judgment of a planning commission—for housing that meets the zoning code, general plan, and environmental standards. Instead, cities like San Francisco mandate discretionary review for nearly every housing development, no matter how small. In Berkeley, neighbors have even appealed a 3-unit development to the city’s Board of Supervisors, who rejected the project even though it met the zoning code.

The state’s Housing Accountability Act prevents cities from rejecting housing developments that do not meet the zoning code. However, many cities enact zoning policies that automatically trigger discretionary review. For example, San Francisco has many zones that automatically trigger “conditional use authorization”, in which the Planning Commission only approves the project if they judge that it “is necessary or desirable to the neighborhood” (SF Planning Department 2017).

This extra planning results in extensive and costly planning review processes for small housing additions or mid-sized apartment buildings that are often more affordable than larger high-rise apartments. Instead, it makes more sense to me to focus limited discretionary planning resources on large apartments that have the biggest impact on the surrounding environment. For whatever limited impacts small to mid-sized developments have on the surrounding neighborhood, it is easy to legislate these into the planning and zoning code. After all, what’s the point of having zoning regulations on paper if we have to individually review every housing development anyway?

Public hearings—like this one in San Francisco—are overused and oftentimes a death knell for housing developments. Image taken from: http://www.sfpublicgolf.org/news.php?news_id=1746

Therefore, my first dream policy is to mandate ministerial development approval for small to mid-sized housing projects that meet the zoning code. This simple procedural change could dramatically reduce entitlement costs for developers, increasing housing supply and affordability region wide. In particular, small to mid-sized developments that cost less to build than large apartment buildings could also increase affordability for low to middle income residents.

As always, there would surely be some political pushback for this change. Neighborhood activists often use discretionary review to bring developers to the table to negotiate for community benefits packages. However, these concerns should be limited by the fact that discretionary review would still exist for large projects. In addition to this, some neighbors will dislike losing local control over development decisions. There is no easy solution to this political opposition—emboldened by overly generous planning policies for local residents to begin with. For this reason, it is critical that the state, regional governments, and executive branches of city governments, which are accountable to broader constituencies rather than local neighborhood coalitions, lead the fight for such policies. We’ve already seen some good news on this front in the Bay Area—from Sacramento (e.g. SB 35) to ABAG to aggressive housing production goals by the mayors of the three big Bay Area cities

II. Reduced Parking Requirements

Parking is expensive, costing tens of thousands of dollars and a significant percentage of the cost of constructing a unit of housing. This is especially problematic throughout the Bay Area, where many opportunities for growth are in infill locations where developers must dig underground or build higher to include parking. Yet cities throughout the region still often force developers to build more parking than what the market demands through outdated planning codes that include minimum parking-to-unit ratios.

Moreover, car ownership in the largest cities in the Bay Area, particularly San Francisco, have been declining recently. A recent survey of 80 housing developments through the Bay Area and found that 28% of the parking—adding up to nearly $200 million in costs—went unused (Tranform 2017). These trends suggest that the region can dramatically reduce the cost of housing while at the same time sufficiently meeting parking demand by simply not mandating that developers build parking. Some of the bigger cities in the region—notably San Francisco and Oakland—have already lowered parking minimums around transit. However, there is a lot of room for more reductions, particularly around BART stations in other Bay Area cities, such as downtown Berkeley or Redwood City, both of which have at least one-to-one unit to parking space ratios.

Despite local regulations that mandate parking minimums, many underground parking garages in Bay Area apartments look like this today. Image taken from: https://www.pinterest.com/boelsander/light-design-parkings/

In general, this reform seems to be less politically challenging than ministerial housing approvals, which are a much more radical departure from CA planning norms. In fact, some recent developments in San Francisco have faced opposition from progressive neighborhood groups because parking ratios have been too high. Despite the political momentum behind this reform, there is sure to be some local opposition from neighbors worried about increased neighborhood parking competition. However, if parking competition is fierce enough, there would also be private incentives for developers to build parking with housing, dulling the increased demand.

III. Increased Renter Protections Through a Land Tax

The two reforms above represent a return to free market principles, which can increase regional housing affordability by responding to market demand. However, the free market can also negatively impact existing renters, especially when prices increase dramatically in the short term due to high demand. Therefore, many CA cities must invest in renter protections to protect existing low-income residents. Aside from a moral justification for protecting residents from displacement, we can justify anti-displacement policies in that society values socioeconomic diversity and housing stability as a public good, worthy of government protection. Typically, the best way to provide public goods is for the government to subsidize this good.

Although the government can use any funds to subsidize renter protections, I propose that they tie these funds to the social value of land through a land value tax. Based on the writings of Henry George, a land value tax is levied on the socially created value of land, separate from the value that the owner contributed to the land. As demand increases to live in the Bay Area, the socially created value of the land increases—through no effort of the existing landowners. In this case, it’s necessary to tax the landowners in order to extract that social value and give it back to the public. In this case, I suggest using the funds to mitigate one of the largest negative effects of this growth—displacement of existing residents. For example, these funds could be used to fund existing renter’s protection enforcement, affordable housing acquisition, or rental assistance programs.

Land value enlarged by increases in the social value of land. Should be taxed! Image taken from: http://www.henrygeorge.org/rem4.htm

Out of the three local policy recommendations, this is probably the most politically difficult. Landowners would likely be vehemently opposed to any tax increases. However, there is a good argument this is a small compensation to pay after years of benefiting from artificially capped property taxes through Proposition 13. Furthermore, tying the funds to affordable housing and anti-displacement programs would likely be politically popular among liberal constituencies, particularly renters.

IV. State Recommendation: Common Sense CEQA Reform

Localities largely have to play by the state’s rules in planning and zoning decisions. One of the most restrictive and problematic of those rules is the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). A by-product of a wave of environmentalism in the 1960s and 70s, CEQA was initially passed with the intent to publicize the environmental impacts of a development and to consider mitigations for negative environmental effects (Fulton and Shigley 2012, p. 180). However, the law gives extraordinary power to opponents of development by allowing anyone to file a lawsuit for any reason, and placing the burden of proof on local governments. This has resulted in decades of CEQA abuse—lawsuits filed by neighbors or labor unions concerned not with environmental impacts but rather with protecting property values or securing union contracts.

In fact, in a review of all CEQA lawsuits filed from 2010-2012, Jennifer Hernandez has found that 2/3 of the housing-related CEQA lawsuits target environmentally friendly infill housing in urban areas (Hernandez, et. al. 2015, p. 63). Once a lawsuit is filed, it can take months or years for a court to reach a decision, during which time the project is stalled. Not only does this time delay supply increases from responding to the market, but it also increases the costs of development so that the project may become infeasible.

Fortunately, there are a number of common sense reforms—summarized well in Jennifer Hernandez’s study—to CEQA litigation that could make a big impact. First, CEQA litigants are able to conceal their identities and reasons for suing a development (Hernandez, et. al. 2015, p. 78). Requiring that litigants both identify themselves and the environmental reason for suing a development would represent an easy change to protect CEQA from non-environmental related abuses. Furthermore, projects can be sued an unlimited amount of times even after a court has upheld the project against previous challenges. Restricting lawsuits after a court has ruled that a project meets CEQA would go a long way towards curtailing abuses. Lastly, many courts that rule in favor of litigants deny housing projects entirely rather than requiring further environmental mitigation or public disclosure, even if the project meets the vast majority of environmental standards. CEQA litigation reform that would allow for more mitigation relief rather than vacating a project altogether would go a long way toward curtailing abuse by litigants that merely want to halt projects for non-environmental reasons. Overall, curbing these abuses would restrict CEQA lawsuits to those truly concerned with environmental impacts, helping lower costs for developing housing statewide and, in particular, in urban areas.

Although these CEQA reform measures make sense, a lot of entrenched interest groups—especially wealthy homeowners and labor unions—rely on abusive litigation to fight against development. The rules surrounding CEQA litigation have been in place for decades and reform disrupting this status quo would surely cause political backlash. However, appealing to the common sense nature of these reforms and targeting abuses of CEQA rather than legitimately environment-related lawsuits could help overcome political opposition. Furthermore, a growing awareness of CEQA abuse is sprouting up among the state’s progressive politicians, supported by pro-development yimbys (“yes in my backyard”).

V. Federal Recommendation: Funding Incentives for Land Use Reform

Lack of housing supply is a large issue in most of the high demand markets nationwide. This lack of supply is, in turn, a result of state and local land use control, where already-existing residents have the private incentive—and the political control—to block additional development. At the beginning of the 20th century, states and localities devised land use controls as a result of power delegated by the federal government. To be more specific, local control over land use is founded on the basis of police power, or the state’s power to regulate to protect the “health, safety, morals, and general welfare” of its inhabitants. This power is given to localities from states, who have this authority on the basis of the 10th amendment, which reserves all government powers not specified for the federal government by the Constitution to the states.

So if land use control authority is local, what can the federal government do? Its role is mainly limited to promoting states to “do the right thin” through example legislation and federal grants. In fact, the Obama administration did just that by proposing $300 million in funding through the Local Housing Policy Grants to regions that supported new zoning and land use regulations to create and expanded, more diverse housing supply (Furman 2015). These were grants proposed to localities to support any new policy—from infrastructure expansion to code writing assistance and implementation—that would reform land use policies to promote development. Although the total amount was a rounding error in the overall federal housing spending, it represents a small but significant step in the right direction. A few million dollars to hire a team dedicated to land use reform might be all a locality needs to make sweeping changes to build more multifamily housing in previously exclusive single-family areas or decrease parking requirements near transit-oriented neighborhoods. In this way, small incentives from the federal government could be enormously impactful to affordability. After all, it was the federal government’s model Standard State Zoning Enabling Act (1922) that contributed to the widespread adoption of restrictive zoning in the first place.

Federal support for land use reform could encounter opposition from Republican members of Congress that are generally less supportive of housing funding. However, the opposition is not guaranteed. This policy would represent a largely market-based approach to housing affordability and barriers to economic growth, which is likely appealing to conservatives.

References

Bialick, Aaron. 2014. “Car-Free Households Are Booming in San Francisco.” Streetsblog San Francisco (blog). August 16, 2014. https://sf.streetsblog.org/2014/08/15/car-free-households-are-booming-in-san-francisco/.

“Conditional Use Authorization.” 2017. San Francisco Planning Department. http://sf-planning.org/sites/default/files/FileCenter/Documents/481-CU%20Application.pdf.

Dineen, J. K. 2016. “In a Wealthy SF Neighborhood, Residents Fight Low-Income Housing.” San Francisco Chronicle. November 16, 2016. http://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/In-a-wealthy-SF-neighborhood-residents-fight-10617213.php.

Fulton, William, and Paul Shigley. 2012. Guide to California Planning. 4th ed. Solano Press Books.

Furman, Jason. 2015. “Barriers to Shared Growth: The Case of Land Use Regulation and Economic Rents.” The Urban Institute.

Hernandez, Jennifer, David Friedman, and Stephanie DeHerrera. 2015. “In the Name of the Environment.” Holland & Knight, August. https://www.hklaw.com/publications/in-the-name-of-the-environment-litigation-abuse-under-ceqa-august-2015/.

Li, Roland. n.d. “As Millennials Reject Car Ownership, Developers Reduce Parking in Projects – San Francisco Business Times.” Accessed November 8, 2017. https://www.bizjournals.com/sanfrancisco/news/2017/07/27/parking-crashes-against-reality-cre-q3-2017.html.

Taylor, Tracey. 2017. “Berkeley’s Bid to Stop New Housing Being Built Overruled by Judge.” Berkeleyside (blog). July 25, 2017. http://www.berkeleyside.com/2017/07/25/berkeleys-bid-stop-new-housing-built-overruled-judge/.

Transform. 2017. “Comparison Report | GreenTRIP Parking Database.” 2017. http://database.greentrip.org/.

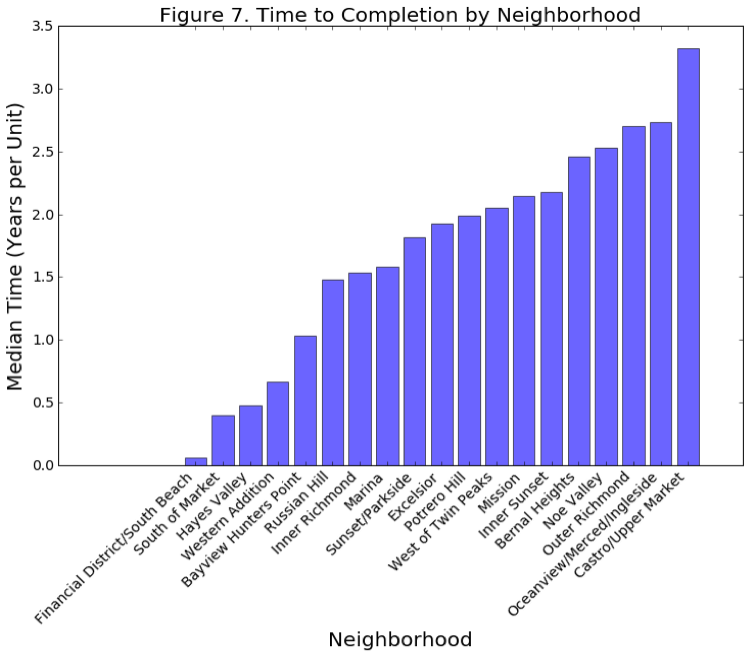

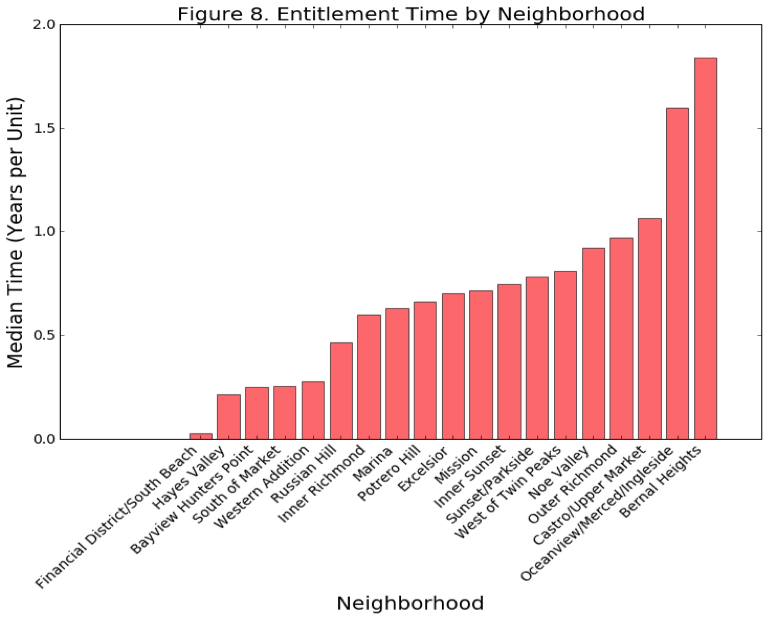

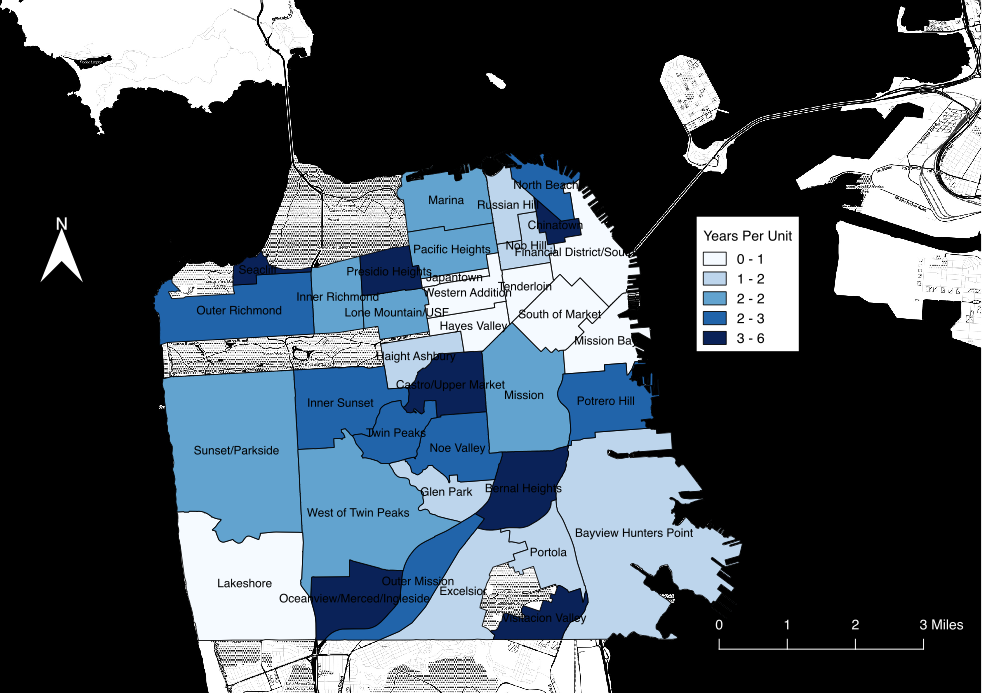

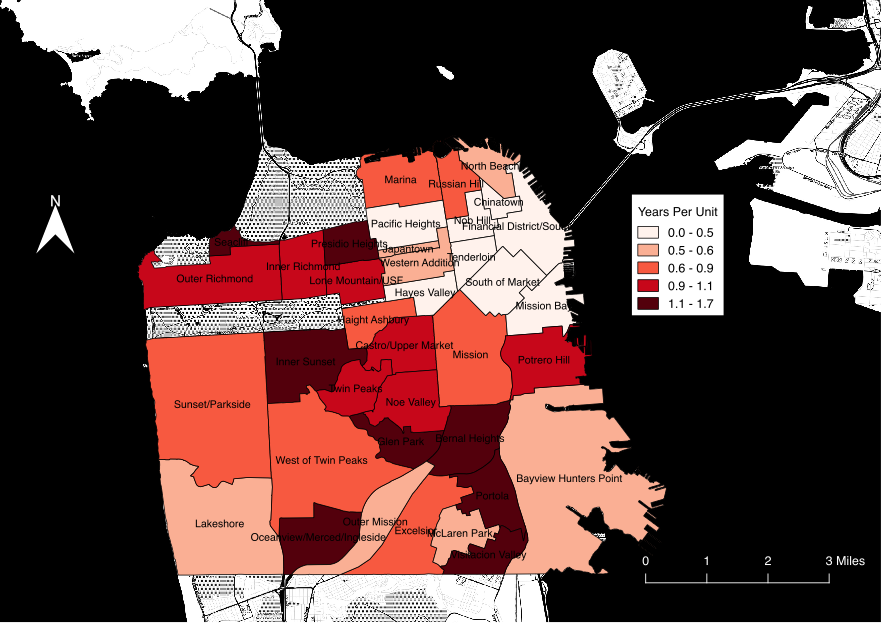

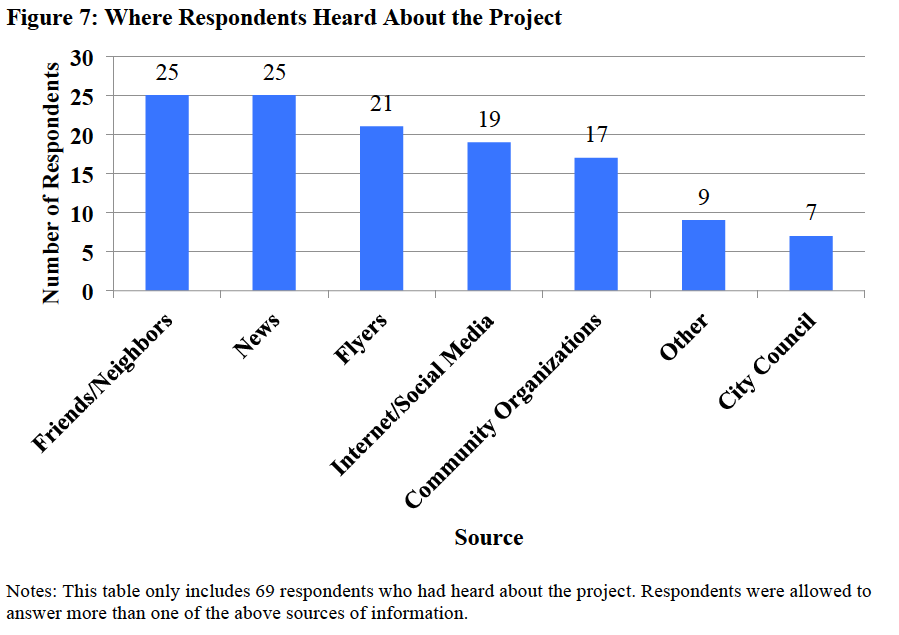

Finally, I explore differences between neighborhoods. For Figures 7 and 8 below, I use the

Finally, I explore differences between neighborhoods. For Figures 7 and 8 below, I use the