Paris has recently made urbanist headlines worldwide for its leadership in transportation planning. Over the course of the past decade, the city has repurposed 50,000 parking spaces into over 800 miles of bike lanes, is planning for hundreds of miles of new metro lines, and just last week started limiting cars travelling through its city center. But on a recent visit to the city, I noticed another remarkable trend of old buildings being converted to new housing. Some of the city’s major social housing developers have made adaptive reuse a central part of their strategy for adding new housing. These projects include buildings of all shapes and sizes, and I thought I’d share a couple here that have really caught my attention.

1. Caserne de Reuilly – Military Barracks to Social Housing Conversion

One of the largest recent adaptive reuse projects is the conversion of the Caserne de Reuilly, former military barracks owned by the French Ministry of Defense, into 582 new units of social and private rental housing. A significant chunk of the project consists of the reuse of the existing buildings, originally built as a mirror factory in 17th century and then later purchased by the French state for barracks. After the barracks were deemed surplus to military needs, the French government sold the site to Paris Habitat, a public housing developer (and the largest social housing developer in Paris), for €40M, a significant discount from the estimated market price of €70M.

Equally impressive to the conversion of the barrack buildings is the construction of several new mid-sized apartment buildings around the perimeter of the property that add new housing and fill in the gaps on the surrounding block. It’s a good example how historic buildings and new construction can fit seamlessly together.

The all-in costs for the project (acquisition + construction) amount to €149M, or about $347,000/unit in US dollars, far below the typical cost of a similar development in most major US cities. Paris Habitat even sold part of the project off to a private real estate owner for market-rate housing. The transformation also includes a new public park in the interior of the block that is now accessible to pedestrians, creating a new walkable through-block connection that had previously been blocked off by the barrack gates.

A final striking aspect of the project is the enormous amount of ground-floor retail, a little over 40,000 square feet in total. This retail, which is very rare to see in American affordable housing projects, includes an eclectic variety of stores, such as a comic bookstore, a hair salon, a grocery store, a doctor’s office, and a 66-space childcare facility.

2. Caserne Exelmans – Police Barracks to Social Housing Conversion

At the other end of the city in the chic 16th arrondissement, another barracks conversion is underway. The former Caserne d’Exelmans, originally constructed between 1907 and 1909, will soon become 50 social housing units, a childcare center with 36 places, and a new transitional housing center with up to 79 spaces. Similar to the Caserne de Reuilly, Paris Habitat is partnering with a government entity, this time the city of Paris, with a ground lease to retrofit the existing building into new housing. The total project budget is €29.6M and includes low-interest loans from the French government and the city of Paris. Although I couldn’t find much information about this one, it’s another great example of reusing historic buildings for future housing.

3. Jean-Jaurès – Parking Garage to Social Housing Conversion

Very much on brand with the city’s movement to repurpose on-street parking spaces, Paris Habitat converted this former parking garage to 149 units of new housing in the 19th arrondissement in 2022. The site was built in 1968 as two residential towers separated by an 8-story garage and offices operated by the car manufacturer Renault. Since its former use, the property fell into the hands of the French national government, who sold the project in 2017 to Paris Habitat to subdivide and renovate.

The development of the new residence consisted of a partial demolition of the old parking garage and a new ground-up development attached to the structure. The concrete slabs of the old parking structure were used as a base to develop 75 new private apartments (sold off to a third party) whereas the new structure, a stunning timber framed building with wood exterior paneling, serves as 74 new social housing units owned and operated by Paris Habitat. Overall, the 74 social housing units were developed for a cost of €24M euros (development + acquisition), or about $385,000/unit.

4. Glacière Daviel – Vertical Addition to and Renovation of an Existing Building

In addition to converting commercial buildings, Paris Habitat is also adapting its residential housing stock to accommodate more units. This is the case with the Glacière-Daviel residences in the 13th arrondissment, which in 2019 saw a vertical addition to add 64 new units on top of the existing buildings. At the same time of the vertical addition, Paris Habitat completely renovated the existing 756 apartments and added 17 new exterior elevators to connect the entire new building together. In total, the building additions and renovations were completed for a total of €65M, or about $102,000/unit.

These vertical additions, known as a “surélévation” in French, are quickly taking off in France as a useful way to pay for the retrofits of old buildings to adhere to new EU environmental standards. One recent startup called Upfactor, specializes in feasibility studies for vertical additions and has consulted for several social housing agencies and cities across the country to assess their housing stock for potential additions. They offer a service of identifying buildings that are both structurally capable to hold and zoned for additional units. In a recent study for the city of Lyon, Upfactor estimated that of the city’s social housing stock, over 400 buildings were suited for vertical additions that could add over 7,000 additional units without expanding their built footprint.

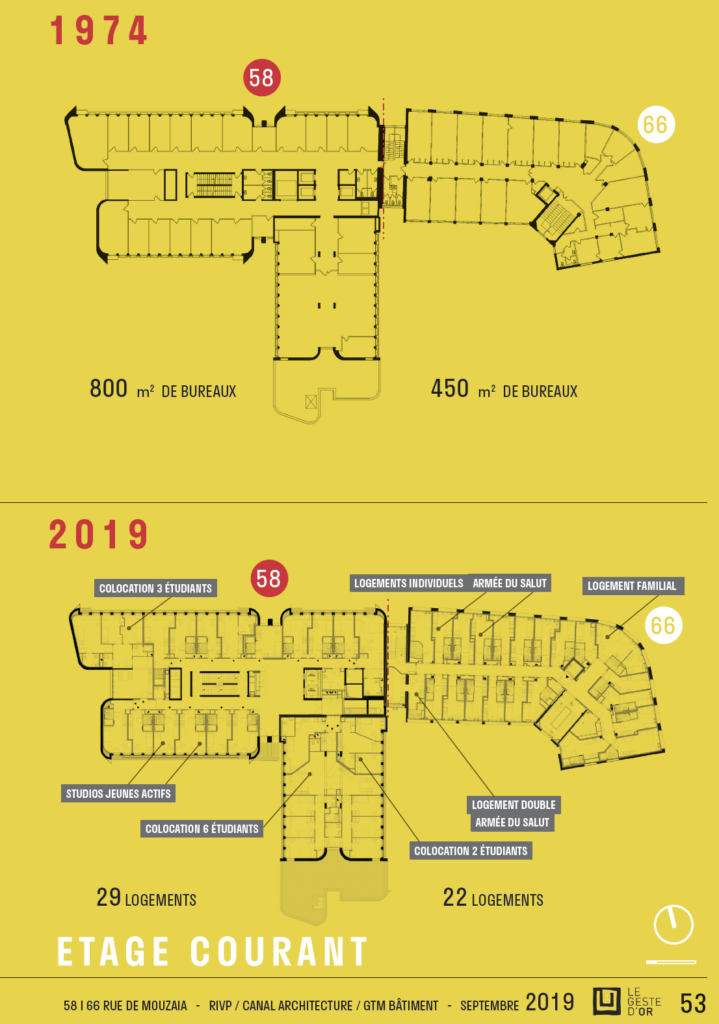

5. 58 Rue de Mouzaïa Résidences – Brutalist Offices Converted to Housing

Social housing developer RIVP converted this office building located in the northeastern 19th arrondissement in 2019. Originally built in 1974 as a rare case of brutalist architecture in Paris, it served as offices for the ministry of health until they moved out in 2010. In 2015, RIVP purchased the site for a steeply discounted €6.7M (about $7.2M) thanks to a 2013 law that discounts publicly-owned sites destined for social housing.

The renovated building is able to fit a lot of new uses, including 168 units of housing, 14 artists working studios, and 90 co-working spaces all in about 88,000 square feet. The units, targeted towards students or young professionals as short-term housing, are small at about 200 square feet each. The development team kept the major corridors and stairwells from the previous office use, leaving behind a double-loaded corridor for the new residential units.

The building was originally designed by the architects Claude Parent and André Remondet and redesigned by Canal Architecture, who have some great photos on their website. I’m very struck by the new windows made with oak wood frames which contrast beautifully with the concrete exterior. This month, the building was officially designated as architecturally remarkable by the Ministry of Culture.

Parting Thoughts

Just as Paris is transforming its streets to prioritize the movement of people over cars, these conversions show a few creative examples of how the city continues to evolve its built environment to house people. That’s not an easy feat in what is already one of the most densely populated cities in the developed world. Paris Habitat, developer of 4 of the 5 projects above, has itself set a target of building 600 new units per year within the city limits.

With an entirely different set of economic and political factors to consider, it’s difficult to extrapolate these Parisian projects to a US context. Nonetheless, some universal lessons do stick out. In most of the examples above, public agencies showed intentional leadership to identify and then sell surplus government buildings to housing developers. They were also not afraid to change the appearance of old buildings if it creates an opportunity to house more people. This are worthwhile lessons for any city considering adaptive reuse as a tool for addressing their housing shortage.